New study reveals rapid pace of ocean acidification in Pacific waters near Hawaiʻi

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa oceanographers have revealed that the ocean is acidifying more rapidly than predicted below the surface in the open waters near Hawaiʻi.

Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere enters the ocean at the surface and has been increasing the acidity of Pacific waters since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution more than 200 years ago. However, a new study reveals how quickly the water is acidifying.

“Ocean acidification has far-reaching consequences for ocean biology and the global climate,” said Lucie Knor, lead author of the study and postdoctoral researcher in the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “We expected some indicators of ocean acidification to be changing more rapidly below the surface because that was what some global studies have previously discovered, but we were very surprised that this was true for every single ocean acidification indicator.”

Burning fossil fuels creates carbonic acid and increases the ocean’s acidity, which can lead to consequences such as weakened coral reefs, harm to shellfish, and impacts on the entire marine food web.

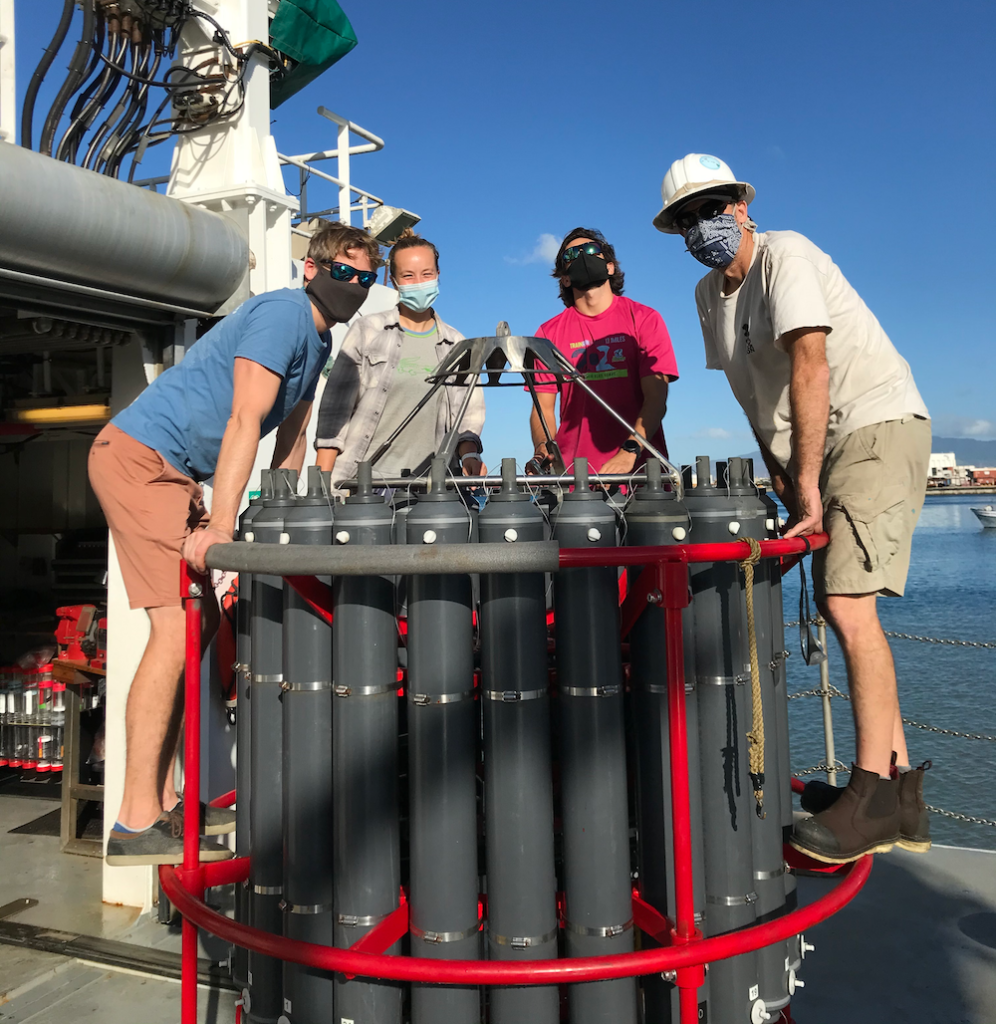

Knor and co-authors analyzed a 35-year record of ocean carbon measurements made by the Hawaiʻi Ocean Time-series program throughout the entire water column—from the surface to nearly three miles deep—at the open ocean field site 60 miles north of Oʻahu at Station ALOHA.

They found that in all layers, there are increases of carbon from natural decomposition of sinking organisms. In some layers, accelerated acidification is associated with fresher and colder waters. Their discovery was published in the “Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.”

“Deeper waters are already naturally quite acidic in the North Pacific, so quickly increasing acidity could negatively impact plankton species and other organisms that live below the surface,” Knor said. “In the long run, these changes in ocean chemistry also make it harder for the ocean to keep taking up more CO₂ from the atmosphere.”

Researchers, fisheries managers, and coral conservationists are concerned with the combined impacts of ocean acidity events and marine heat waves, which have increased due to unusual conditions in the ocean and atmosphere, and strong, multi-year El Niño events.

Subsurface waters at Station ALOHA are formed farther north in the Pacific, so changes in seawater properties impacted by evolving environmental conditions in other areas of the North Pacific are then transported by ocean currents into the deeper layers of the ocean around Hawaiʻi.

“We illustrate that regional-scale changes in source water chemistry and circulation are substantial drivers of the subsurface intensification of ocean acidification around Hawaiʻi,” said Christopher Sabine, co-author of the article and School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology oceanography professor.

Currently, the research team is investigating the carbon specifically from human-made sources in the water column at Station ALOHA and how that is changing over time in different layers.