Some hikers blame ‘rancid’ toilet facilities for norovirus outbreak on Kalalau Trail on Kauaʻi

As the Hawaiʻi State Department of Health continues with its survey to determine the cause of the norovirus outbreak that has affected at least 50 visitors on the Kalalau Trail along the Nāpali Coast on Kauaʻi, some are blaming the virus on the state’s facilities that they say are unsanitary.

One hiker also said a hospital’s failure to report her case contributed to the spread.

The entire 11-mile Kalalau Trail, from Kē‘ē to Honopū in the Nāpali Coast State Wilderness Park, has been closed since Sept. 4 and will remain closed until at least Sept. 19 due to the virus. The state Department of Health says the issue was most likely caused by a hiker, who entered the park already infected with the very contagious norovirus and then became ill, which started the spread of the infection.

Big Island resident Danielle Burr was part of a group of 13 that hiked to the campsite at Kalalau Beach on Aug. 29. About 36 hours later, she said people “began dropping like flies.”

The norovirus causes acute gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach or intestines. Common symptoms are vomiting, diarrhea, nausea and stomach pain. Most people with norovirus get better within 1 to 3 days; but they can still spread the virus for a few days after, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Signs of the virus began when Burr witnessed one of her friends spring out of his hammock to throw up. Shortly after that, Burr saw other people getting sick, including a person lying on the ground next to the public toilets.

“It is stinky over there,” she said. “You would not want to lay over there unless you had to.”

A person from another campsite asked Burr’s group if they had any imodium, an anti-diarrhea medication. Burr estimated 14 people at the site were experiencing symptoms.

Burr said around 1 a.m. on Sept. 1 she was hit with the virus that caused her to vomit between 50 and 60 times in an 8-hour period.

“It was violent,” she said. “All pride was lost. I didn’t even have the wherewithal to care about being embarrassed. Everyone can see it coming out of both ends. Everyone heard me all throughout the night. And the bathrooms are so far away, and I could barely walk 10 feet.”

Burr was medevaced off the trail via helicopter several hours later, at around 9:30 a.m. She said she knew of only one other medical evacuation that occurred a couple of days later, but the majority of people hiked the trail or took a boat back to town.

Burr was taken to Wilcox Medical Center, where an ER doctor suspected she had leptospirosis, a disease spread through the urine of infected animals. She was treated with antibiotics and IV fluids. Being wary of the medical costs, she left as soon as she was stabilized.

Despite telling doctors and nurses at the hospital that she was one of many others that were sick on the trail, Burr says no one from the hospital reported the incident to the state Department of Health.

“I was thinking I’m going to see the park is going to be shut down, or they’re going to have some type of announcement. And two days had passed and I saw nothing,” she said.

Two days later, Burr called the state Department of Health to report the illness and was given a testing kit that confirmed norovirus. That afternoon, the trail was shut down.

In an email response, DOH communications specialist Kristen Wong said the illness would have been considered an “urgent report,” requiring medical professionals to have called the department to report the incident. She deferred questions about the reason for the lack of reporting to a hospital representative, but a representative from Wilcox could not immediately be reached for comment.

Aside from the reporting, Burr says there needs to be better signage, education and maintenance of the composting toilets, which she called “smelly” and “poorly maintained.”

Additionally, when people started feeling sick, Burr said most of the campers could not make the 10- to 15-minute trip to the toilets, which resulted in defecation in the woods without sanitation.

“I think that the distance of the toilets resulted in open defecation and that open defecation is absolutely what made this so widespread, and it is a huge part of the issue,” she said.

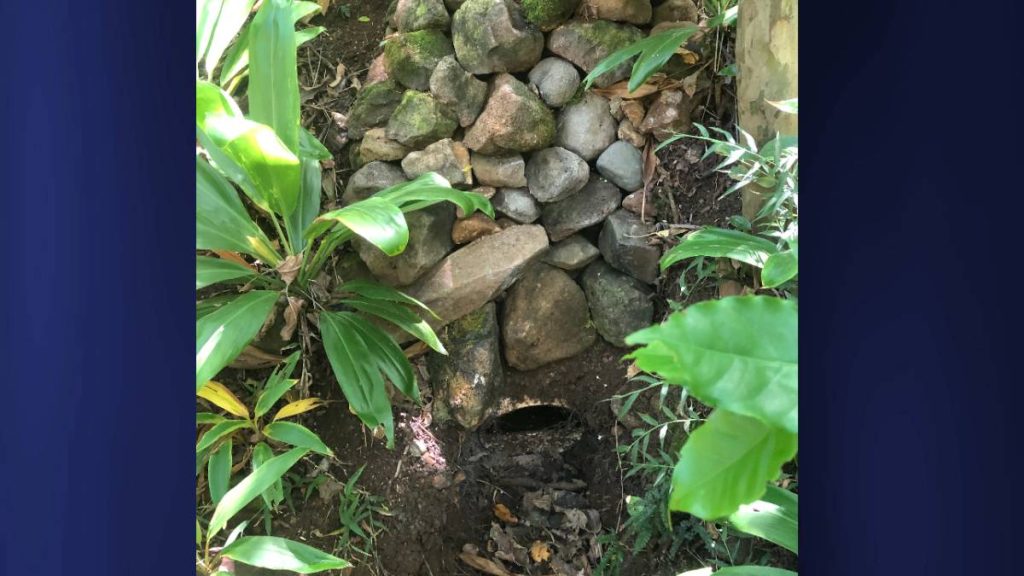

She noted that the toilet closest to the campsite was locked and not in use.

North Shore resident Megan Wong made similar comments about the toilet situation on the trail, blaming the virus on “a lack of management by the state.”

Wong says that from her own experience, it’s not uncommon for the toilet closest to the campsite to be locked, and that she often finds poop piles, toilet paper, and tampons around the camp because people are not aware of other restrooms due to the lack of signage; or they are too disgusted by their conditions to use them.

“If they’re not functioning correctly, that they smell so rancid that people don’t want to go in them or can’t go in them, that’s the reason they need to take responsibility,” she said of the state.

However, state Department of Land and Natural Resources Communications Director Dan Dennison said that any unhygienic facilities or areas can be blamed on the park’s visitors.

“Issues of trash and dirty toilet facilities have everything to do with people at Kalalau not practicing good and safe camping practices,” Dennison said in an email response. He added that staff have picked up items in the past including coolers, queen-sized mattresses, BBQ grills, and other large items that had been illegally brought in by boats or Jet Skis.

The trail has three “comfort stations,” Dennison said, which are equipped with one or two toilets at various points along the trail — Hanakapiai, Hanakao and Kalalau. He says the toilets are cleaned around the first of each month, when employees also pick up trash and rubbish before it is bagged and flown out in helicopter sling loads.

Cleaning the bathrooms includes shoveling effluent into 55-gallon barrels that also are flown to final disposal. The comfort stations also are cleaned and restocked, Dennison said.

The one-seat restroom is currently locked because it has no additional capacity. The two-seat comfort station was cleaned and thoroughly disinfected last week and will be cleaned and disinfected a second time prior to reopening of Kalalau, Dennison said.

In recent years, Dennison said the amount of trash has gone down significantly due to concerted efforts to diminish illegal activity and transportation by the Division of State Parks and the Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement.

Megan Wong, who says she is a lineal descendant of Native Hawaiians from the Kalalau Valley, believes the state should put more resources into maintenance of the facilities to protect the land.

Since 2020, Wong and her family have been part of a volunteer effort to clean up the trail, which she says has been “so desecrated and disrespected,” largely from squatters living illegally in the area.

Despite the state’s enforcement efforts leading to a decline in the number of squatters and illegal businesses, some people continue to live there.

Burr had mentioned she was camping next to a woman who was living at the site with her 8-month-old baby for over a month. The woman had given birth to the baby in the stream at Kalalau.

“She trusts that spirit will provide,” Burr said, but added that the woman relies on other hikers to “take pity” on her and offer to help her out.

Burr later learned through Facebook that the woman also contracted norovirus and became really sick. Burr, who is also an occupational therapist, has been using a Kalalau Trail Facebook group with over 32,000 members to share her experience and connect with others that became ill.

“There was shit and puke all over that campsite. It was a matter of time before this happened,” she said.

Despite the sickness, Burr plans on returning to the trail in the future for another camping trip. “It’s the most beautiful, magical place in the world. Even after the experience I’ve had, I will go back,” she said.

The state Department of Health is asking all park visitors that entered the park between July 1 and Sept. 4 to complete the survey, available here, which aims to determine the source of the outbreak.

Corrections:

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the time that Danielle Burr was medevaced off the Kalalau Trail. It was around 9:30 a.m., not 4 a.m.