Is Mauna Loa getting ready to erupt?

It’s not a matter of if, but when.

“Yes, Mauna Loa will erupt again,” Katie Mulliken, a geologist with the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, told Big Island Now.

It’s been nearly 40 years since the volcano’s last eruption, the longest Mauna Loa has gone without one. But heightened activity under the snoozing giant’s caldera during the past month begs the question: Is an eruption of Mauna Loa coming soon?

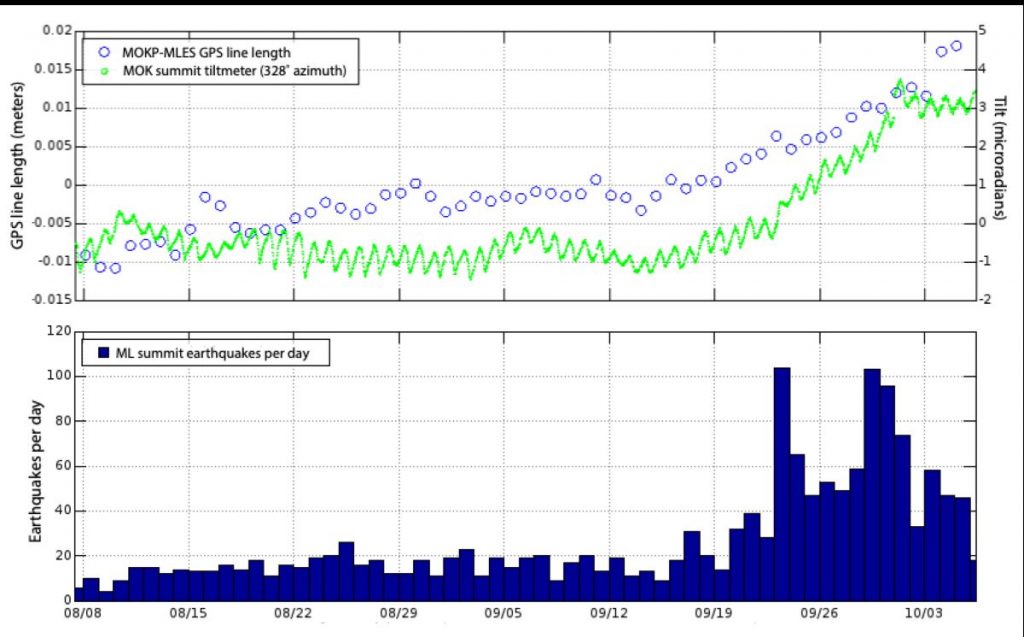

The observatory reported Oct. 5 that earthquake activity under the 13,681-foot-tall volcano has increased to 40 to 50 small-magnitude temblors a day since about mid-September, peaking at more than 100 quakes a day Sept. 23 and 29. That’s a significant difference from 5 to 10 earthquakes a day in June, and even the 10 to 20 quakes per day in July and August.

Most of the quakes have occurred beneath Moku‘āweoweo, Mauna Loa’s summit caldera, at depths of 1 to 2 miles. The majority have been smaller than magnitude-2.

The alert level for the volcano remains at advisory and the aviation color code has not changed from yellow.

The recent uptick in activity, however, led the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory to change how often it issues updates for Mauna Loa from weekly to daily. It also caused Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park to close the Mauna Loa summit backcountry until further notice.

But none of that means an eruption is likely to happen soon or that one is expected.

“Other signals, such as seismic tremor, that would indicate that an eruption is imminent, have not been observed,” Ingrid Johanson, a research geophysicist at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, wrote in this week’s “Volcano Watch.”

The spike in seismic activity is related to inflation of a magma chamber beneath Mauna Loa’s summit. That inflation, or expansion, also has increased during the past two weeks.

“The unrest is likely caused by renewed input of magma into Mauna Loaʻs summit reservoir system,” according to Friday’s update. “As the reservoir expands, it is triggering small earthquakes directly beneath Mokuāʻweoweo caldera and in a region just to the northwest of the caldera.”

Magma at deeper levels of more than two miles has been detected by continued increase in upward movement and extension measured by instruments on the ground at the summit. Shallower magma input was the likely culprit behind the inflation during the last two weeks of September.

Hawaiian Volcano Observatory instruments recorded nearly 40 temblors from Thursday to Friday 2 to 3 miles below Mokuāʻweoweo caldera and 4 to 5 miles under upper elevations of Mauna Loa’s northwest flank. Both regions have historically been seismically active during periods of unrest of the volcano.

The volcano has been at the advisory alert level since 2019 and displayed similar elevated activity and inflation of the summit region from late January to late March in 2021 with no eruption. Additional periods of heightened unrest have also happened during the past 38 years since Mauna Loa’s last eruption in the 1980s. The current episode of unrest actually began in late 2014 and then waned in 2017-18 before increasing again in 2019.

“We expect additional shallow seismicity and other signs of unrest to precede any future eruption, if one were to occur,” the observatory said Sept. 29 in its then-weekly Mauna Loa update.

No other signs of unrest have been detected during this most recent spike in activity at the summit.

Mauna Loa has erupted 33 times since 1843, averaging one eruption every five years. The volcano has remained relatively quiet since its last eruption in the 1980s, its longest period of repose in the past 200 years.

Mauna Loa’s last eruption in March 1984 began with the number of earthquakes under the volcano rapidly spiking to 2 to 3 per minute shortly before 11 p.m. on March 24. By 11:30 p.m., strong tremors indicated magma was getting close to the surface. The eruption began at 1:30 a.m. on March 25 at the summit.

The eruption began suddenly and followed a three-year period of slowly increasing earthquake activity beneath the volcano. The main activity eventually migrated to fissures in the volcano’s northeast rift zone.

Four parallel lava flows at one point moved down Mauna Loa’s northeast flank at speeds as fast as 90 to 215 mph. Lava came within about 4.5 miles of Hilo during the eruption.

“Smoke from burning vegetation, loud explosions caused by methane gas along the advancing flow front and the intense glow at night all contributed to a growing concern among Hilo’s residents,” the US Geological Survey wrote. “Would the lava reach the city?”

Lava would not reach Hilo, and by April 14, 1984, no active flows extended more than 1.25 miles from the remaining vents. The eruption ended the next day.

“The rapid onset of extreme unrest leading to eruption in 1984 is typical of the Mauna Loa eruptions that have been observed in the last two centuries,” Johanson wrote.

She added that while technology has advanced since the last eruption, giving the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory more detail about periods of unrest than ever before, forecasting an eruption still remains difficult.

That means the situation can change quickly.

“In addition to rapid onset, eruptions that migrate down either of Mauna Loa’s rift zones tend to be high volume and resulting lava flows can move quickly from their eruptive vents downslope toward the ocean,” Johanson wrote. “The combination of rapid onset, large lava volumes and fast lava flows can make Mauna Loa eruptions particularly hazardous.”

The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory continues to monitor Mauna Loa, Earth’s largest volcano, carefully and will issue updates if conditions change. Hawai‘i County Civil Defense also provides hazard updates when warranted.

For more information about the current monitoring of Mauna Loa, click here.