Best case? Projected unprecedented acidity of Hawaiian waters will impact coral within next 30 years

Ocean waters around the globe are acidifying as they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, threatening coral reefs and other marine life.

Acidification of waters around the main Hawaiian Islands is expected to follow suit; however, a new study led by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa oceanographers reveals it will reach unprecedented levels within the next three decades.

That news comes at the same time as the National Marine Fisheries Service announced critical habitat designations for five threatened coral species living in the Pacific Ocean.

The agency’s final rule also protects 92 square miles of marine habitat around American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, the Pacific Remote Island Areas and Hawaiʻi.

Researchers in professor Brian Powell’s laboratory group at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology used advanced, fine-scale computer models to project how ocean chemistry around the main Hawaiian Islands might change during the 21st century.

The extent and timing of the changes varied depending on the amount of carbon added to the atmosphere.

Increased ocean acidification is harmful to marine life, leading to issues such as weakening the shells and skeletons of organisms such as corals and clams, amplifying the effects of existing stressors and threatening ocean-based ecosystems.

Corals are experiencing dramatic global declines because of climate change, ocean acidification, pollution and overfishing.

An estimated 50% of coral reefs worldwide have already been lost to climate change and about one-third of reef-building coral species are at risk of extinction.

“We found that ocean acidification is projected to increase significantly in the surface waters around the main Hawaiian Islands, even if carbon emissions flatline by mid-century in the low emission scenario,” said lead author of the new paper Lucia Hošeková in a release from the university.

The School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology research scientist added that the team found in all nearshore areas, the increases will be “unprecedented compared to what reef organisms have experienced in many thousands of years.”

In the high‐emission scenario, the team found ocean chemistry will become dramatically different from what corals experienced historically, potentially challenging their adaptability. Even in the low‐emission scenario, some changes are inevitable, but less extreme and occur more gradually.

The team also calculated the difference between projected ocean acidification levels and the acidification corals in a given location experienced in recent history.

They discovered that various areas of the Hawaiian Islands could experience acidification differently. For example, windward coastlines consistently exhibited future conditions that deviate more dramatically from what coral reefs experienced in recent history.

“We did not expect future levels of ocean acidification to be so far outside the envelope of natural variations in ocean chemistry that an ecosystem is used to,” said study co-author Tobias Friedrich in the release.

The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Department of Oceanography research scientist said this is the first ocean acidification projection specifically for Hawaiian waters to document that.

Previous studies showed that a coral exposed to slightly elevated ocean acidity can acclimatize to those conditions, thereby enhancing the coral’s adaptability.

Researchers remain hopeful, as some organisms have shown signs of adapting to the changing waters.

Data and information provided by the new University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa study helps researchers, conservationists and policymakers understand the future challenges facing Hawai‘i’s coral reefs and provides information for preserving these critical ecosystems for future generations.

The team will continue to investigate the future changes in Hawaiian waters, specifically, heat stress, locations of possible areas where coral could be more sheltered from stress and changes to Hawai‘i’s fisheries.

Powell said the study’s results show potential conditions of acidification corals could experience; however, that extremity varies based on the climate scenario the world follows.

Best case scenario: corals will be impacted, but it could be manageable.

“This is why we continue new research to examine the combined effects of stresses on corals,” he said in the release. “This study is a big first step to examine the totality of changes that will impact corals and other marine organisms and how it varies around the islands.”

Some of the impact is already being felt, but Center for Biological Diversity staff attorney David Derrick was breathing a sigh of relief earlier this week after seeing the National Marine Fisheries Service finally safeguard five threatened Indo-Pacific coral species with critical habitat protections.

“These designations give struggling corals a much-needed fighting chance. Protecting corals’ homes is a crucial step toward reversing the crisis of reef die-offs,” Derrick said in a release announcing the designation. “These ecosystems support ocean biodiversity around the world, and we need to do much more to save such vulnerable species and all the ocean critters that depend on reefs.”

The Pacific coral species covered by the new designations and where they occur in the United States are:

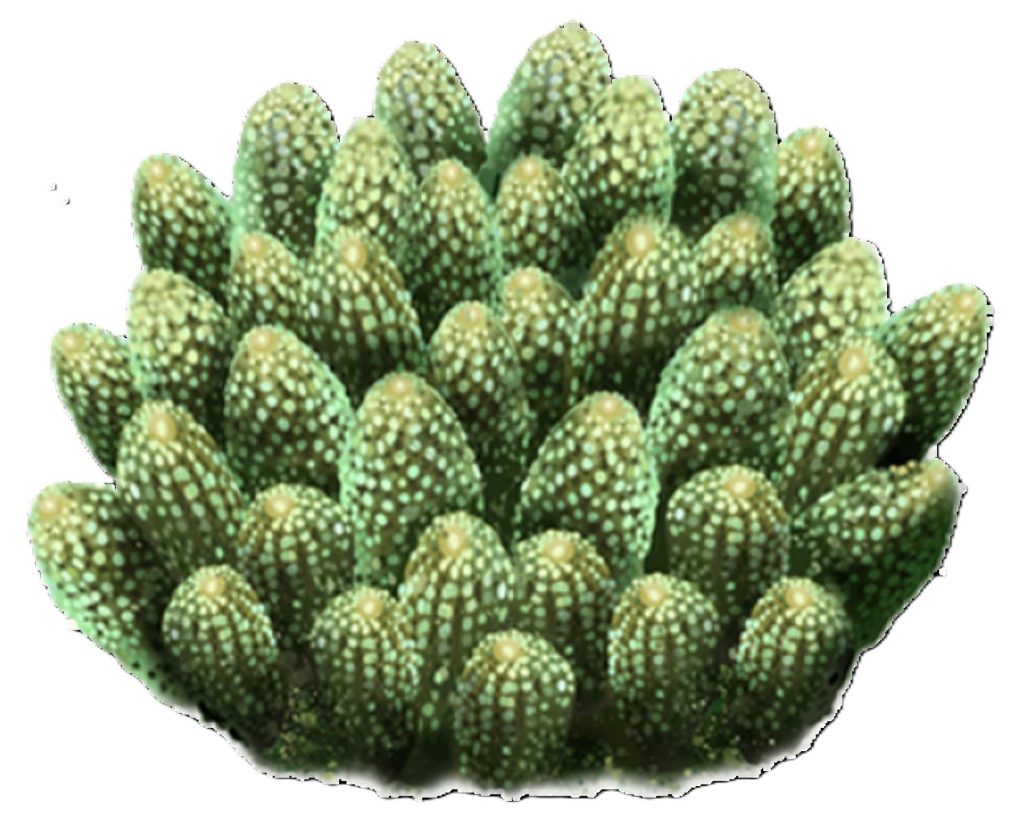

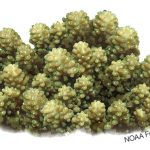

- Acropora globiceps: Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, the Pacific Remote Island Areas, and at Lalo (French Frigate Shoals) in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

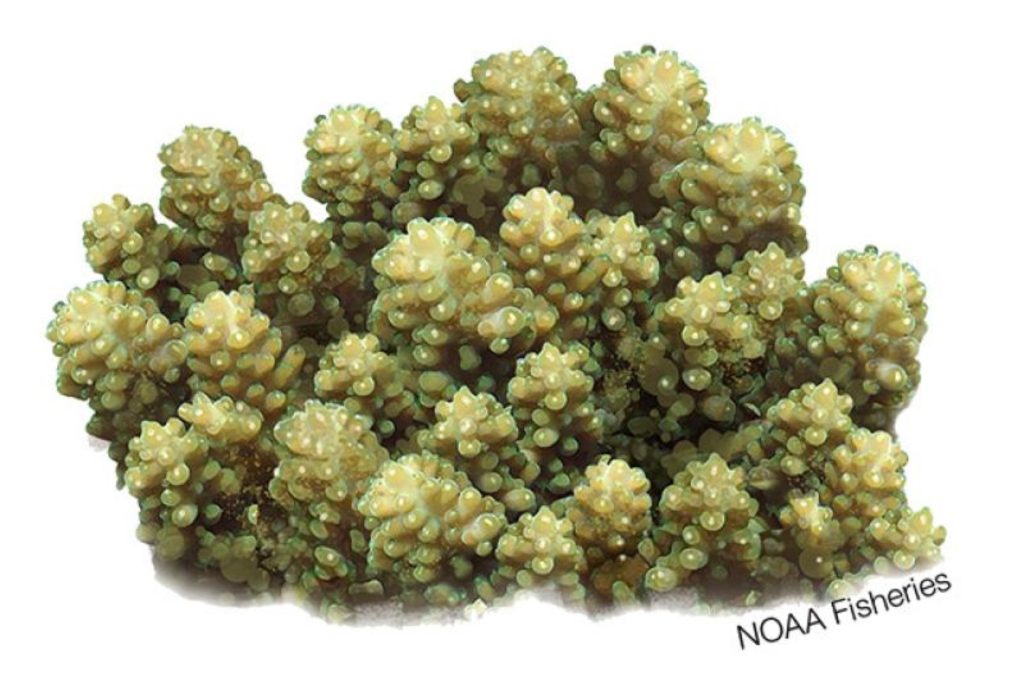

- Acropora retusa: American Samoa and the Pacific Remote Island Areas.

- Acropora speciosa: American Samoa.

- Fimbriaphyllia paradivisa (formerly Euphyllia paradivisa): American Samoa.

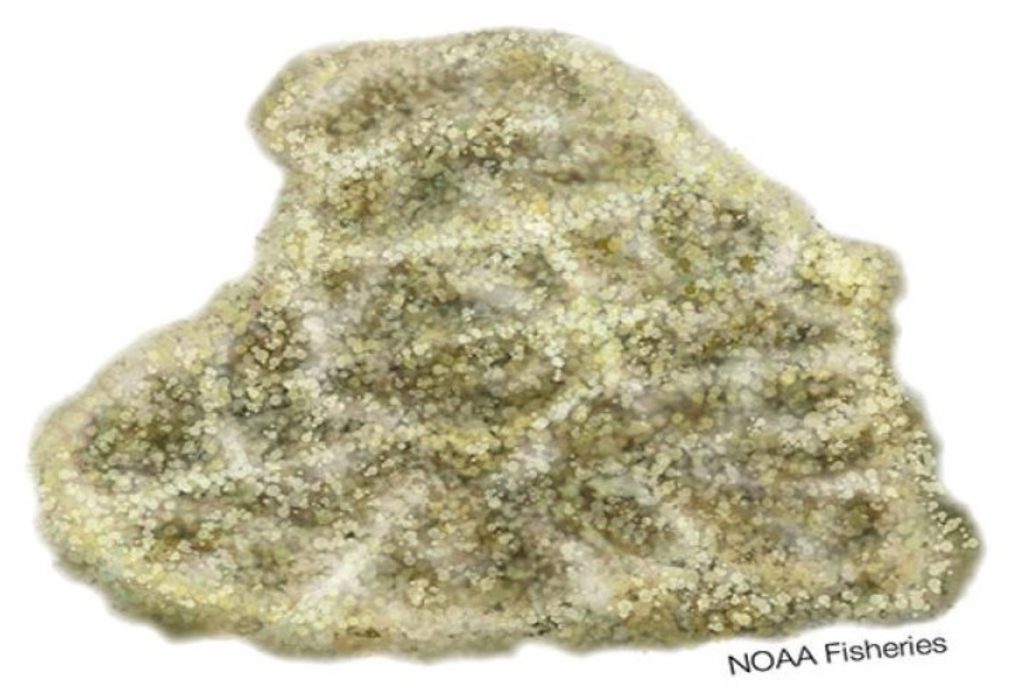

- Isopora crateriformis: American Samoa.

The designations follow a March 2023 lawsuit filed by Center for Biological Diversity against the National Marine Fisheries Service for failing to finalize protections for 12 threatened coral species throughout the Caribbean and Pacific, including the five that received habitat designations this week.

All the species were listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2014 but did not receive the critical habitat designation the law requires.