I Ola Wailuanui advocates alternative vision to new hotel at former Coco Palms Resort

Out-of-state developers plan to transform the derelict site of the former Coco Palms Resort – a once-glamourous vacation destination destroyed by Hurricane Iniki in 1992 – into a new, upscale 350-room hotel.

But that fate of the Coco Palms property, located in Wailuā on the East Side of Kaua‘i, is not certain.

Earlier this year, the State Board of Land and Natural Resources slapped Utah-based developer Reef Capital Partners with a “Notice of Alleged Violation & Order,” following allegations of unpermitted clearing.

These and other alleged violations are now under investigation by the State Department of Land and Natural Resources, which has the power to revoke the developer’s leases to three state-owned parcels comprising 16 acres of the Coco Palms property, according to a local newspaper.

The Kaua‘i County Council also recently debated obtaining Coco Palms’ two fee-simple parcels, either through purchase or condemnation and eminent domain.

Community group I Ola Wailuanui – which opposes the construction of a new hotel at Coco Palms – is ramping up community outreach to share its alternative vision for the site.

I Ola Wailuanui members Pua Rossi, a professor of Hawaiian studies at Kaua’i Community College, and Fern Holland, an environmental consultant, spoke at the latest Kaua‘i Climate Action Forum, a monthly online series sponsored by local environmental groups.

I Ola Wailuanui wants to obtain the former Coco Palms site to create a center of Hawaiian education, cultural practice and community based environmental & land-use stewardship.

“Wailuā, or specifically Wailuanuiaho’ano, [holds] deep importance to not just Kaua‘i but to all of Hawai‘i,” Rossi said. “It is a uniquely special and sacred area that represents an extremely important part of Kaua‘i’s history and sustainability.

“This area is noted for its social, religious and political importance, much of which is tied to the ocean and the water resources of the river, truly making this … a fat and wealthy land that provided abundant food resources.”

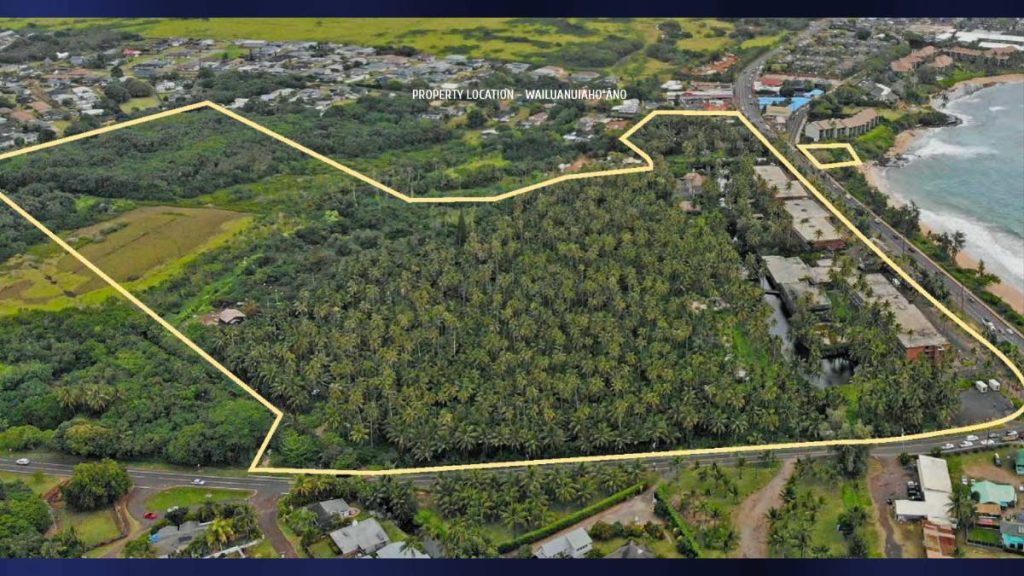

Wailuanuiaho’ano is a stretch of coastal land within Wailuā, running between Hanamāʻulu and the Wailuā Houselots residential area. The former Coco Palms Resort is located within its boundaries.

According to Rossi, the region became a seat of political power on Kaua‘i in the 14th century, due to its strategic location. In the 19th century, it was known as the favorite home of the last king of the island, Kaumuali‘i, and his favorite wife, Deborah Kapule.

Today, the Coco Palms site remains the documented home of the island’s oldest coconut grove, ancient fishponds and burial sites.

“We recognize the value that this site holds … We definitely want to preserve it for future generations,” Rossi said.

Coco Palms Resort also is historically significant, most famously hosting Elvis Presley in the musical icon’s 1961 film “Blue Hawai‘i,” he said.

Holland, meanwhile, argued against a new hotel’s construction on environmental grounds.

“The construction of a $250 million, 350-room hotel would have an estimated impact of around 10,000 metric tons of carbon, which is about [the same as] 3,500 cars per year of construction,” she said.

Preservation of the area’s wetlands – which are home to endangered bird species – would better serve the Kaua‘i community, she added.

How can I Ola Wailuanui’s ambitions come to fruition? The group hopes to eventually purchase the Coco Palms property, saying it needs at least $25 million to do so. With that end in mind, it’s seeking an “angel donor” with deep pockets, and small donations. A November 2022 pledge drive amassed more than $200,000 in promised contributions.

When asked why I Ola Wailuanui’s plans for the former Coco Palms site are not hyper-specific, Holland explained the group wants more community input and buy-in: “It’s going to take a huge collaboration of people that work on these issues: fishpond practitioners, farmers, construction, government – people who care.”

Holland said it is not developing, but “de-developing this site down into a green space, a park and a cultural and agricultural system.

“I think a detailed plan has to be put together of how we get to that point of really showing this place. But the place does that for itself. We’re not really creating something, we’re just restoring and preserving something that’s already there.”