In a landlocked home in Kalāheo, Kauaʻi artist Desmond Thain is up to something fishy.

Surrounded by goats, chickens and a burgeoning garden, the 39-year-old practices a distinctly marine craft: gyotaku — the Japanese art of fish printing.

While working on a new creation using a fresh-caught tako (octopus) on his lānai one drizzling afternoon, Thain said: “Art is art, and you cannot put a definition on what true art is. But the original art was created by hand. That’s how gyotaku was created. Because Japanese fishermen in the 1800s needed a way to record their subject.”

The Oʻahu native grew up as a young boy infatuated with sharks. He’d visit marine art galleries and libraries to draw his favorite species out of picture books. He also got an education in other cultures, traveling to Japan, Cuba, Barbados and Jacksonville as the child of a U.S. Marine, before returning to O‘ahu at Marine Corps Base Hawai‘i in Kāneʻohe.

Thain spent his teenage years falling in love with spearfishing.

“All of my friends – for years – told me to gyotaku my fish and I said, ‘I’m cool, I don’t need to do that,’” Thain said.

But while in college, Thain changed his mind. The day had come when he didnʻt want to eat a personal-best trophy fish, but to memorialize it.

“You don’t want to freeze it. You’re just like, ‘I need to capture this memory, somehow. Its size. Just how special it is,'” he said.

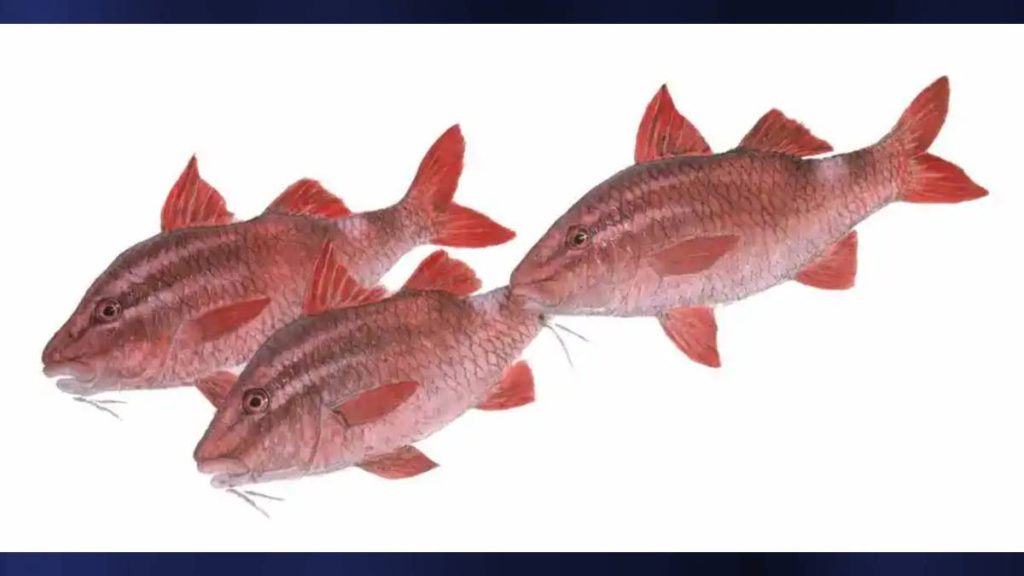

Thain’s first special fish was a kumu (whitesaddle goatfish). It’s a prized, delicious creature with scarlet and rosy scales. Thain decided to commemorate the important catch by taking it to a local gyotaku artist, who brushed the fish with ink before imprinting its image on a sheet of paper.

The resulting product – a copy of the fisher’s catch – is both a sportsman’s trophy and an art piece. In that sense, it can be compared to a taxidermied boar’s head hanging on a cabin wall.

But Thain was disappointed when he received his kumu print. The end result was too simple, in his opinion, and failed to capture the vitality of the fish when alive. So armed with the do-it-yourself sensibility he possesses to this day, Thain set out to make his own gyotaku.

“I was in college at the time and I could barely afford anything other than food,” Thain said. “So I bought cheap craft paper, cheap acrylic ink and some cheap value-pack brushes.”

Thain eventually graduated to professional art supplies and bigger fish, including ahi (yellowfin tuna) and marlin. Those around him took notice of his burgeoning skill and distinct style.

Thain’s friend Colin Hazama, an avid spearfisher and chef who’s appeared on Food Network competitions “Guy’s Grocery Games” and “Alex vs America,” asked Thain in 2013 to print an omilu (bluefin trevally).

Thain snapped a photograph of his completed work and uploaded it to Facebook. When he awoke the following morning, he was shocked to find the omilu image had spurred dozens of comments from strangers hoping to commission Thain themselves. He’d effectively become a professional artist overnight.

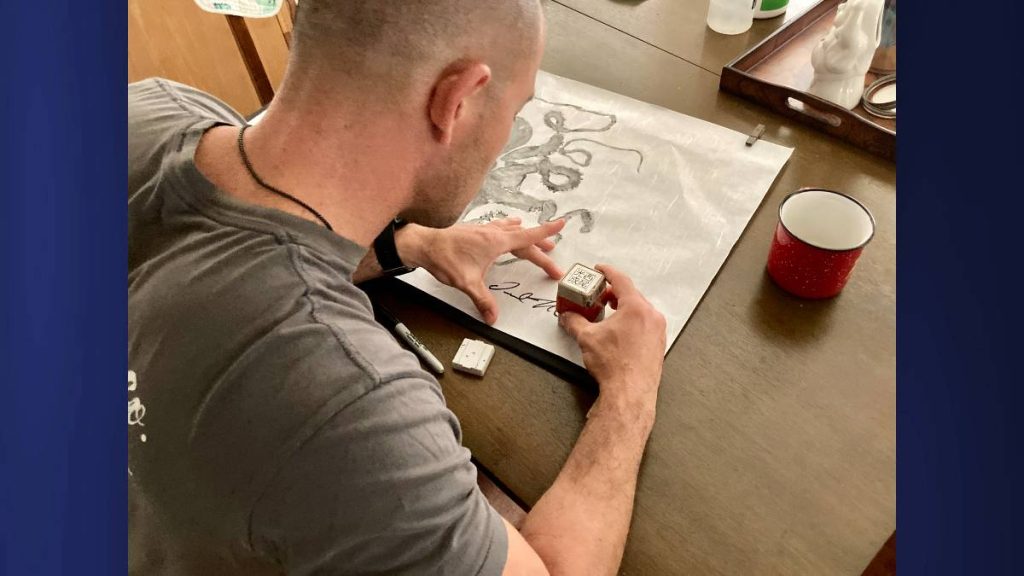

Over the years, Thain has honed his craft. On that drizzling afternoon, Thain caught the tako he printed in waters off Poʻipū. The animal, while dead, took on new life as Thain positioned its eight tentacles in an almost spiral pattern.

Thain uses a Japanese horsehair brush to tenderly paint his subjects with traditional sumi ink made from cedar soot.

“You could also do this with ink taken from its own ink sac,” Thain noted while painting the rainy-day tako.

He then – carefully, using his body to block a sudden gust of wind – draped the inked tako in unryu (cloud dragon paper) made from mulberry pulp and fiber. It remains strong even when wet.

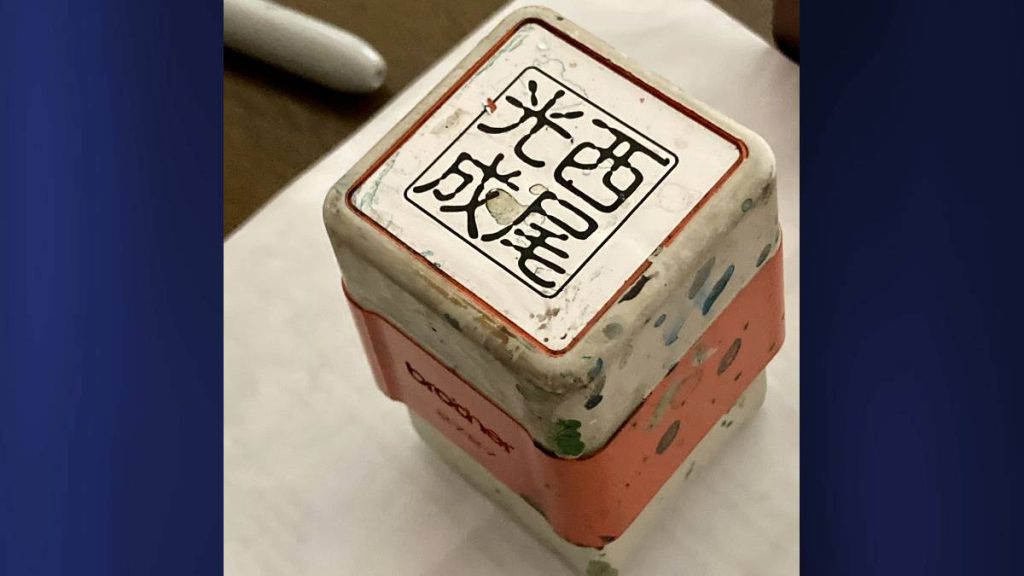

A few moments passed before Thain then peeled the unryu away, revealing a copy of the tako recently pressed beneath it. But Thain’s work was not done. He added subtle highlights with white paint before signing his name with a black Sharpie marker, then making his signature again with a red hanko stamp.

“That’s been a traditional way of finishing artwork for centuries and centuries in East Asia,” said John Szostak, associate professor of Japanese Art History at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. “If you see an artwork that doesn’t have a stamp on it like that, there’s sometimes questions about whether this was actually something the artist intended to have out there in the world as a finished work or not.”

Thain’s Sharpie-and-hanko ritual places old and new, side by side.

To create a gyotaku art piece takes about one month to complete from start to finish, as Thain typically only paints on weekends.

Thain’s friend Hazama, who now owns and operates the upscale catering service C4 Table, said: “What is unique about spearfishing, as opposed to regular fishing, is you’re in the domain of the fish – where their habitats are.”

Hazama frequently spears fish that later appear in his dishes: “It’s a rush to spear a trophy fish, to know the hunting tactics and techniques to bring that fish closer to you … it’s a lot of adrenaline and excitement.”

Hazama finds gyotaku captures the thrill of that underwater world on paper.

“Being able to actually see it on a print showcasing the actual colors and the actual liveliness of the fish while it’s in water [is amazing],” he said.

Thain moved to Kaua‘i in 2019, lured by friends’ reports of good fishing. He works as a Kaua‘i Police Department officer and balks at the term “professional artist” when it’s applied to himself – despite having art for sale in multiple storefronts throughout the state.

“I feel like I’m a new artist, still, in the galleries. I learn something new every time,” he said. “I never thought I’d get to the point where people ask me to sign their prints.”

But people do ask, whether they’re buying originals, giclée prints or attending one of Thain’s occasional gyotaku workshops. Some wealthy vacationers even hire Thain to lead private lessons from the comfort of their resort suites.

Thain’s clientele has expanded since he became a professional artist overnight 10 years ago. Fishers who want to immortalize prize catches now do business with Thain alongside aquatic and fine art collectors, and tourists who snorkeled with certain fish while on vacation in Hawai‘i.

Package carrier and spearfisher E.J. Bukoski owns several Thain originals, alongside works made by other gyotaku artists.

Each print depicts a tako caught by Bukoski, who lives on the south shore of Kaua‘i. It’s his favorite catch and he still remembers the first one he brought to Thain. It weighed seven pounds.

“I brought it to him within hours of capturing it … It made a really good print. After he added all the colors to it, it was mind-boggling,” said Bukoski.

Bukoski thought he’d never catch a gyotaku-worthy tako again. But he found himself back at Thain’s door a few years later, to commission another print.

Bukoski asked Thain to print the tako as if it were falling through the water column, and Thain delivered.

“He captured the image I had in mind,” said Bukoski.

Bukoski can recognize a Thain print by its extraordinary realism.

“It takes you there, like you’re actually there with that image. When you turn, it’s like it’s looking at you and still following you,” he said. His comment could be applied to the Mona Lisa.

Despite Thain’s personal success and the apparent popularity of the art form among Hawaiian fishers, gyotaku remains on the periphery of the mainstream art world.

“They’re not collected in museums, they’re not for sale in any of the art galleries here in town that I know,” said Szostak, speaking from Honolulu. “They seem to be a real niche thing.”

Brian Wyland, nephew of well-known aquatic artist Robert Wyland, is the owner of Wy’s Galleries in Hale‘iwa on the north shore of O‘ahu. He has chosen Thain as his gallery’s sole gyotaku artist.

Thain’s prints routinely cause a stir beneath the ʻōhiʻa trees holding up Wy’s Gallery ceiling. Most folks who cross the building’s threshold don’t know what gyotaku is, but leave as fans of the form, according to Wyland.

“You can see the level of skill that Desmond has in his art. He’s phenomenal,” Wyland said.

Wyland, like Hazama before him, let slip something the self-effacing Thain did not share when first interviewed for this article: he’s begun to print land animals and plants, in addition to the creatures of the sea.

“He started doing florals. We’ve got a palapalai fern; we have a big monstera leaf that he did; we have a bird of paradise in there,” Wyland said. “Desmond is creative enough to expand outside of just printing fish.”

One of Thain’s Instagram accounts features pictures of hand-painted pheasant and rooster prints.

“I always try to have a super humble attitude and have a mentality where I can learn, even from somebody at my workshop,” Thain said. “But at the same time, you know, I do impress myself.”