Volcano Watch: Scientists explain the early lava flow of Mauna Loa’s 2022 eruption

The 2022 Mauna Loa eruption — the volcano’s first in 38 years — began just before midnight, at 11:21 p.m. on Nov. 27. The first caldera floor fissures were visible in webcams; however, the activity flowed south, outside of the view of the webcams, in the initial hours of activity.

Official statements from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory noted that initial vents were within the caldera. But at the same time lava flows were reported visible from Kona.

Indeed, Kona residents could see lava flows descending the western flank of the volcano and they were concerned, feeling that lava was outside of the caldera. In hindsight, it seems appropriate to explain what the observatory personnel knew in the first few minutes of the eruption and why Kona residents were able to see the first lava flows.

Most people are familiar with Mokuʻāweoweo—the inner caldera at Mauna Loa. However, there’s also an outer caldera, which is a geologic term indicating that less obvious mapped faults designate a much larger caldera feature than Mokuʻāweoweo.

This is also true at Kīlauea. For example, most people think of the Kaluapele as the “giant crater” that Crater Rim Drive mostly encircles, but the outer caldera boundary of Kīlauea caldera extends north to the opposite side of Highway 11. When one drives past the entrance to Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, they are driving within the outer caldera of Kīlauea.

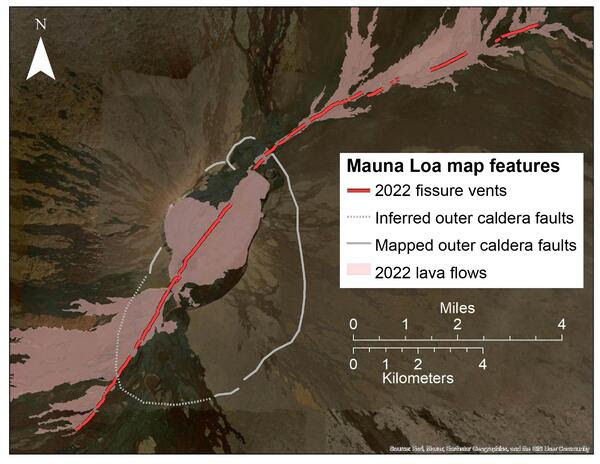

Mauna Loa’s southern outer caldera is buried under lava flows from the past centuries (see white dashed line on map). Three distinctive pit craters dominate this area from north to south: South Pit in Mokuʻāweoweo, Luahohonu and Luahou. These pit craters are within the outer caldera, and not part of the Southwest Rift Zone.

The western rim of the outer caldera coincides with the inner caldera—we have not found circumferential faults to the west. The white line on the map indicates the northern, eastern and southeastern portions of the outer caldera.

The approximate boundary between the caldera and the Southwest Rift Zone is where these circumferential cracks cross the rift zone. Fissures that cross these circumferential cracks would indicate that the eruption is migrating into a rift zone. Sometimes fissures run right up to the outer caldera boundary and then head in the opposite direction (as happened during eruptions in 1935, 1942 and 1984).

This is an important concept because Hawaiian Volcano Observatory stated that initial 2022 fissures were restricted to the summit area. Yet, overnight photographs from Kona showed lava flows descending the western slope—so how was this possible? Shouldn’t the lava be hidden from view by the western topographic edge of the caldera?

The observatory’s use of the phrase “summit region” may have caused confusion for some Kona residents who thought the observatory was referring to the “inner caldera.” The flows seen from Kona were coming from 1.8 miles of fissures in the south outer caldera. When lava is erupting from this area it is visible because there are no major caldera walls obscuring the view of the western flank.

Later mapping revealed that 1.2 miles of fissures extended from the outer caldera into the uppermost extent of the Southwest Rift Zone, with minor lava being emitted from those fissures. In total, the 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa saw 5 miles of fissures open across the central and southern outer caldera floor during the night of Nov. 27 and 28.

By the first eruption overflight at dawn on Nov. 28, all fissures in the inner caldera, southern outer caldera, and the uppermost Southwest Rift Zone had stopped erupting and were incandescent glowing cracks. And, a new set of fissures had begun to form on the Northeast Rift Zone. The three lowest elevation fissures were erupting during the initial overflight and named fissure 1 to 3. Fissure 4 opened two days later, on Nov. 29, 2022.

In total, 11 miles of fissures spanned the uppermost Southwest Rift Zone, the southern and central outer caldera, and the Northwest Rift Zone during the 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa.

To learn more about Mauna Loa’s 2022 eruption, click here.

Volcano Watch is a weekly article and activity update written by scientists and affiliates with the U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.