Nearly five years ago, the staff of the U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory was forced to move from its facilities near the caldera rim of Kīlauea volcano on the Big Island.

The lava flows during the volcano’s 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption — which inundated parts of lower Puna and destroyed the homes of more than 700 families — didn’t touch the place the observatory had called home since the 1940s. But the eruption caused a partial collapse of Kīlauea’s summit that structurally damaged the facilities beyond repair.

The observatory has since had multiple temporary locations in Hilo, Kea‘au and Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, which at times has made it more difficult to coordinate the monitoring, observing and researching of the island’s volcanoes. Staff members have been able to keep the network of instruments operating, it’s just not as convenient as having everyone and everything in one place.

But now a new permanent home is in the works.

Construction is expected to start this year on a research campus in Hilo that will not only house the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory but also the Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, another U.S. Geological Survey group that has made Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park its home since the 1970s. The research center focuses on the study of biological resources in Hawai‘i and other locations around the Pacific, promoting management and conservation.

U.S. Congress has appropriated about $60 million for the project, which should be completed within 24 to 26 months after construction begins.

“It will be great to have everybody back together in a single facility and then have all of our things available,” said Ken Hon, the observatory’s Scientist-in-Charge. “There’s a lot of stuff we’ve had in storage that we haven’t been able to really utilize to its full extent.”

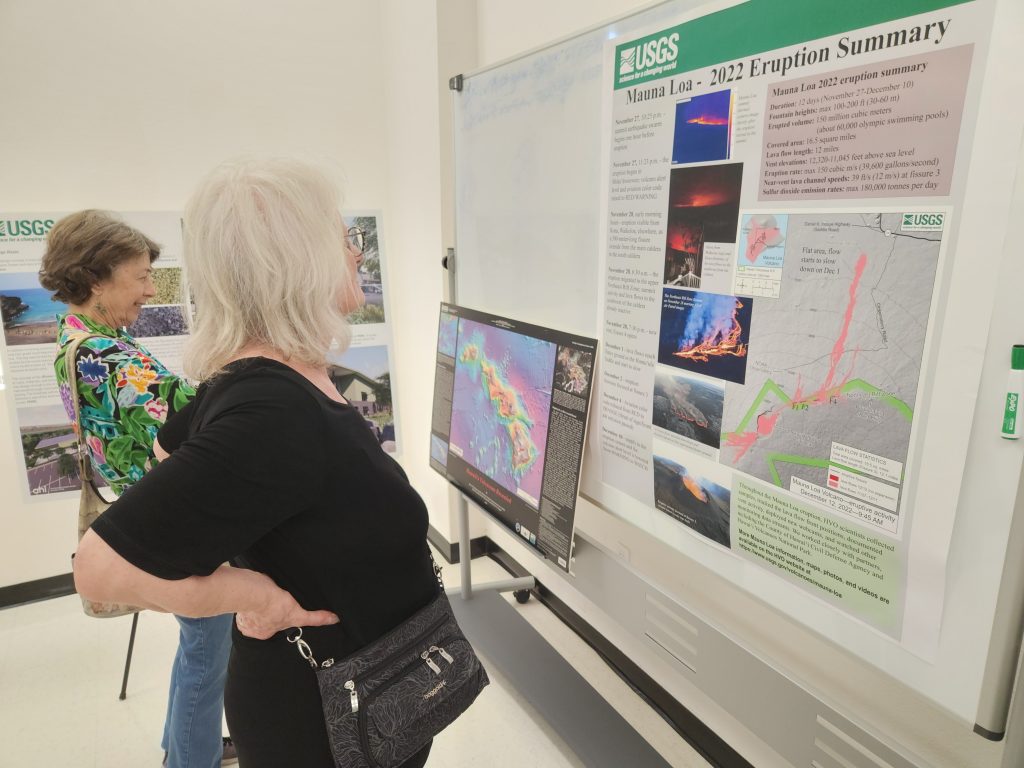

An informal, two-hour open house was hosted Wednesday evening to give the community a chance to learn about the new facility and check out its design. Hon and other officials with the observatory and the research center, including its interim director Bob Reed, were available for questions while people perused informational displays highlighting everything from what each agency does to the architecture of the new campus.

It’s been a long process. While the initial plans for a new facility began in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic set everything back, “like it did for everybody,” according to Hon. It wasn’t until early 2021 when the architects were brought onboard that the serious planning got underway.

“Those of us who will be lucky enough to work at this new facility are thrilled to see the project moving ahead,” said Mike Zoeller, a geologist and mapping specialist with the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

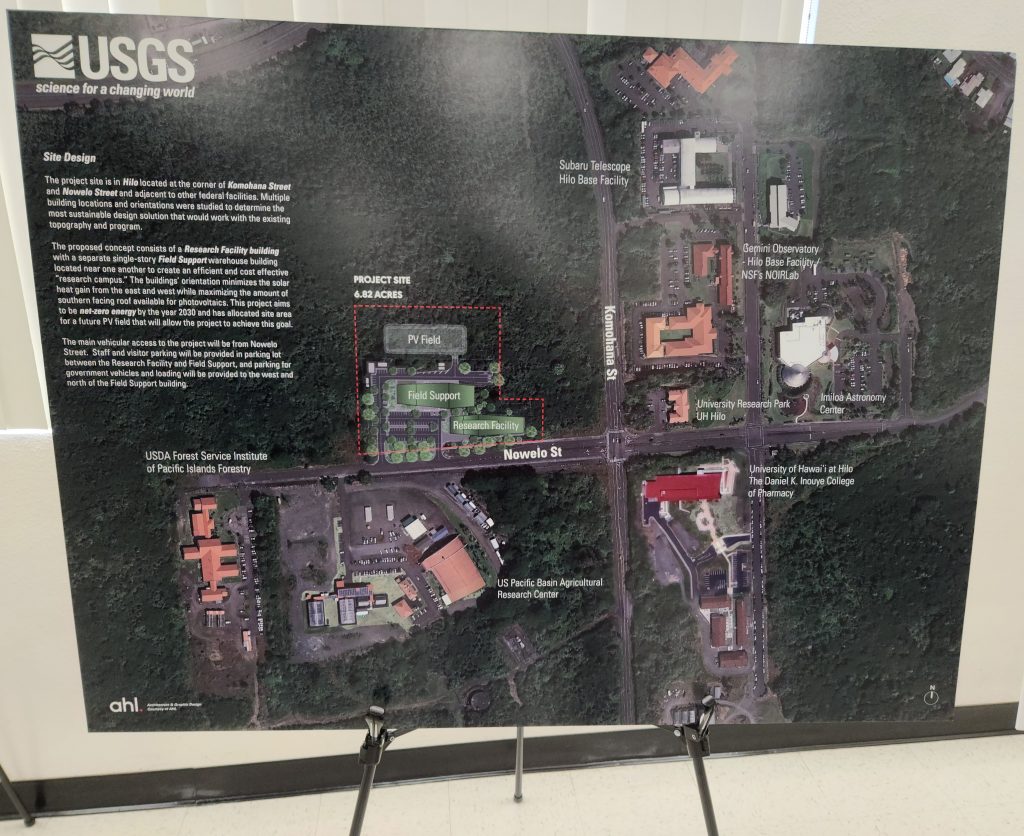

The complex will sit on 6.8 acres of state-owned land at the corner of Komohana and Nowelo streets in Hilo, adjacent to other federal and science agencies, including ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center. The complex also will be near the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. It will consist of a two-story research facility building with a separate one-story field support warehouse.

There will be enough laboratory and office space to accommodate about 80 staff members from both U.S. Geological Survey entities, and the facility will also include an observation lanai from which Maunakea and Manua Loa can be seen. It will be in a location where radio communication between the facility and instruments at Kīlauea and Mauna Loa will be maintained, allowing the observatory to continue to receive data remotely.

“It’s a very good location,” Hon said.

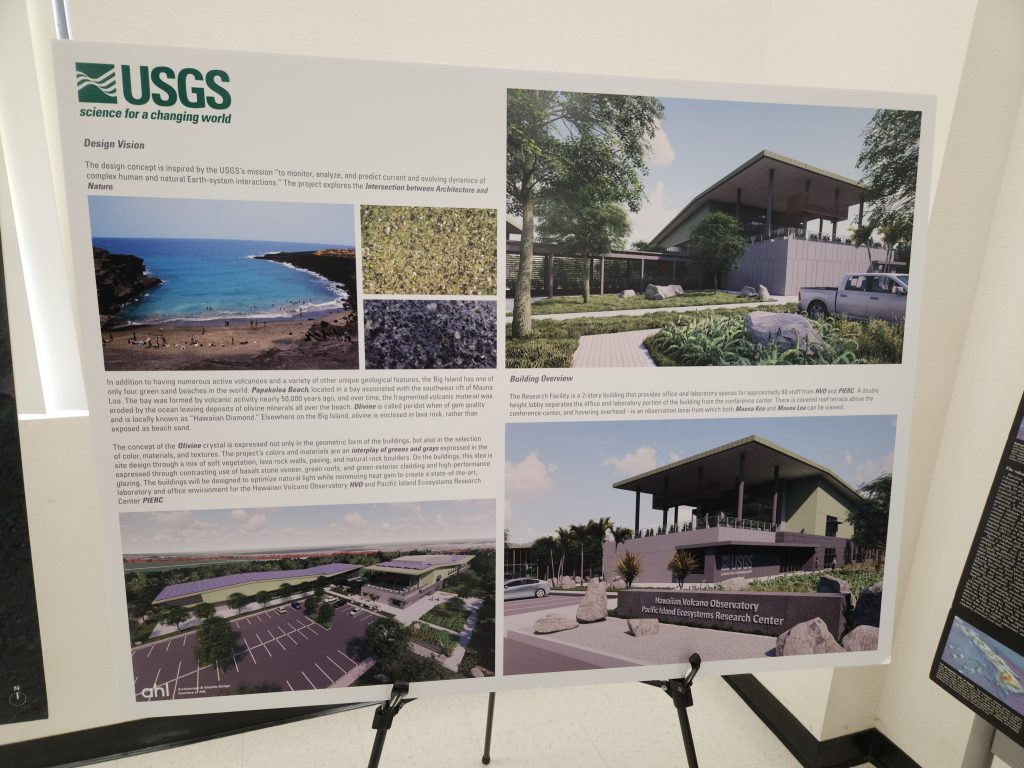

The new state-of-the-art facility’s design concept was inspired by the Geological Survey’s mission: To monitor, analyze and predict current and evolving dynamics of complex human and natural Earth-system interactions.

Martin Smith, an architect and branch chief for U.S. Geological Survey facilities project management who is overseeing the design of the complex by Oʻahu-based Architects Hawai‘i, said the research campus will explore the intersection of science, nature and architecture. Olivine crystal was used as a starting point for the facility’s geometry, colors, materials and textures.

Olivine, which is called peridot when of gem quality and also known as “Hawaiian diamond,” can be found encased in lava rock or in sand at Big Island beaches — especially at Papakōlea Beach near South Point, one of only four green sand beaches in the world.

The bay where the beach is located was formed by volcanic activity nearly 50,000 years ago on Mauna Loa’s Southwest Rift Zone. Over time, the ocean eroded the volcanic material, leaving deposits of olivine minerals all over the beach, giving it a green hue.

An interplay of greens and grays will be expressed through a mix of soft vegetation, lava rock walls, paving and natural rock boulders in the complex’s landscaping as well as basalt veneer and green roofs and exterior cladding on the buildings. The design also optimizes natural light.

The facility aims to have net-zero energy consumption by 2030, meaning its total energy use would be equal to the amount of renewable energy created on-site. An area at the research campus is allocated in the design for a future photovoltaic solar panel field.

Hon said the observatory staff is excited about the design. He said both U.S. Geological Survey agencies were asked what their needs were and the architects came through. The facility also includes spaces that will allow the two agencies to take advantage of being in a more public and accessible location.

“I am especially excited by the sustainability initiatives that have been incorporated into the design, and the commitment to restore native flora on the property — which is presently overrun with invasive species,” Zoeller said.

Reed said he left it up to the architects to make the new facility “pretty.” His main concern was the amount and layout of lab space and the design came out better than he could have imagined.

“The primary opportunity for us is to have modern laboratory spaces that aren’t just cobbled together from whatever we could do,” he said.

The complex is going to be an architectural landmark for Hilo, Zoeller said, and in many ways will be more advanced than other U.S. Geological Survey facilities on the mainland.

An environmental assessment and anticipated finding of no significant impacts have been prepared for the project and the public can provide feedback by clicking here. Questions about the draft environmental assessment can be emailed to jsizemore@usgs.gov.

“Big Island residents live in a dynamic environment, with active volcanoes and a changing climate impacting its diverse ecosystems,” said last week’s “Volcano Watch” article by the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. “The new [U.S. Geological Survey] facility in Hilo will provide a cutting-edge space for scientists to do their work on these fundamental aspects.”

The new location also will provide and encourage opportunities for collaboration between the two Geological Survey entities, which have separate but related missions. Both strive to better understand the complex natural world.

“There’s two different science centers, and they’ve never lived together in the same building,” Smith said, adding the facility’s design includes many spaces where staff members of both will interact — including break rooms, connecting stairways and shared loading areas. “They’re going to be almost forced to collaborate with each other just by living in the same building. So it’s really a good thing for us because we’re creating this multi-disciplinary science facility for sharing.”

The facility and its location also will be a boon for working with students and faculty at UH-Hilo and the public. Reed said the two groups might not have a lot of common ground on research projects, but they definitely can collaborate to provide a lot more opportunities for students.

Hon said it was important for both agencies to be near the UH-Hilo campus so students and faculty could be involved.

Reed added that once they are in the new facility, it will allow for more student interns and public activities, seminars and lectures that will be much easier for people to attend.

And while the staffs of the two agencies will no longer be able to look out their windows at the Kīlauea caldera or the native animals and plants at the national park, Reed said the new complex is a “supercharging for science” with increased interactions with the public, each other and UH-Hilo .

Zoeller said: “Our new headquarters will bring everyone and everything back to a proud home once again.”