Research finds Papahānaumokuākea could be lost breeding ground for humpback whales

New research by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other scientists raises an important question: Does more than one population of humpback whales occupy the Hawaiian archipelago?

Whales are born to travel. As a migratory species, Hawaiʻi koholā (humpback whales) travel thousands of miles annually between Hawaiʻi and Alaska. Hawaiʻi humpbacks are born in late fall or winter in and around the shallow, warm waters of Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary They make the long trip to cooler Alaska waters to feed during the summer months, and then travel back to the sanctuary in late fall to breed and give birth.

But the whale-friendly Hawaiʻi archipelago extends beyond the inhabited Hawaiian Islands, and includes Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, a chain of islands and atolls more than a thousand miles to the northwest. There, banks and seamounts provide ideal whale habitat, and the monument is along the migratory path from Alaska. Could more koholā spend their winters there as well?

The answer is yes, according to research recently published in “Frontiers in Marine Science” by NOAA and other scientists.

“Based on recordings of whale song, our research reveals that nearly the entire Hawaiian archipelago is visited by humpback whales during the winter and early spring months,” says the paper’s lead author Marc Lammers, research ecologist with the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. “We documented an abundance of koholā in Papahānaumokuākea.”

The remote atolls, banks, and seamounts of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument are difficult to access, with challenging conditions during winter months when koholā are present. On-site research during this time is difficult, if not impossible. Anecdotal sightings of whales have been rare.

For years, it was commonly thought that humpback whales did not have a presence in the monument. Since 2006, researchers have used sound monitoring to track long-term trends in biological and human-influenced activities in Papahānaumokuākea.

This is much safer and more economical than vessel-based monitoring, and involves putting stationary moored microphones in the water to record sounds such as whale song. In 2007, breeding and calving activity of humpback whales was documented for the first time within Papahānaumokuākea.

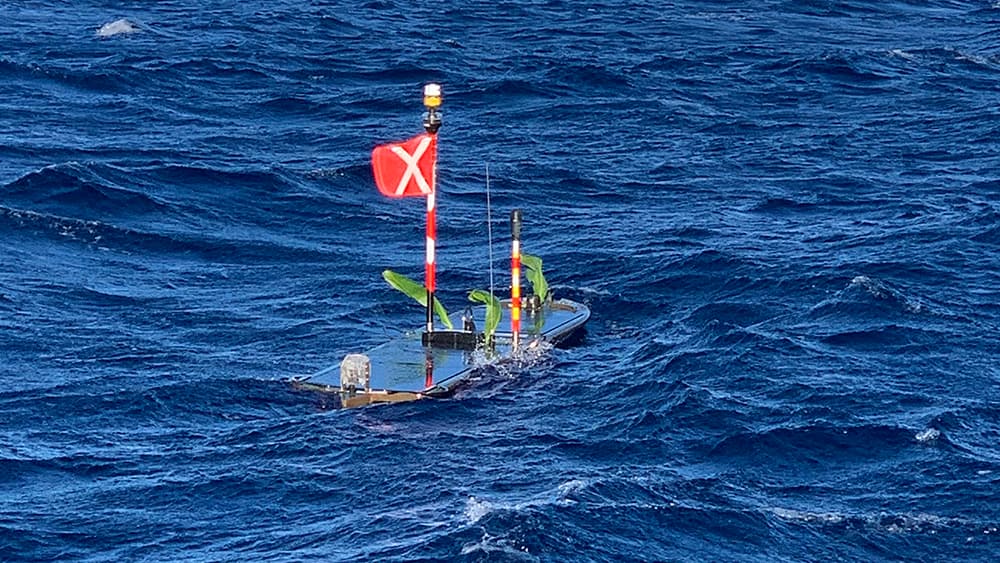

In 2020, the Wave Glider, a remotely operated surface vehicle equipped with sound recorders, traveled 2,600 miles over 67 days, recording the presence of humpback whales throughout the monument. Scientists used this new tool in their quest to study humpback whales as part of NOAA and the U.S. Navy’s Sanctuary Soundscape Monitoring Project called SanctSound.

The result: High and sustained seasonal chorusing levels of whale song measured off the inhabited Hawaiian Islands and every location sampled in Papahānaumokuākea.

“Song occurrence patterns suggest that there may be more structure in the distribution of whales in Papahānaumokuākea than previously known,” Lammers said. “It raises questions about whether multiple populations occur across the archipelago.”

In the monument, song prevalence was highest at Middle Bank and gradually decreased further to the northwest, reaching a minimum at Gardner Pinnacles (Pūhāhonu). However, song occurrence increased again at Raita Bank, remaining high between Raita Bank and the Northampton Seamounts.

Among the locations monitored with moored recorders, the highest and most sustained seasonal chorusing levels were measured off Maui followed by Lalo (French Frigate Shoals), Hawaiʻi Island, Middle Bank, Oʻahu, Kauaʻi, ‘Ōnūnui, ‘Ōnūiki (Gardner Pinnacles), and Manawai (Pearl and Hermes Reef), respectively.

Was the lack of singing at Gardner Pinnacles just a gap in a single population’s distribution across the monument, or is it a “break” between the locations of two different populations of humpbacks?

There are 14 distinct humpback whale population segments worldwide, and data has shown that humpbacks have very strong fidelity to migratory destinations. The portion of the population that breeds in Hawaiian waters is known as the Hawaiʻi distinct population segment. In 2016, it was deemed recovered and removed from the list of endangered species. Other population segments, however, are still listed as endangered.

One of those, the endangered western North Pacific humpbacks, have proven to be a mystery to scientists, since their breeding grounds have not been fully determined. Studies have suggested remote breeding locations such as the Northern Mariana Islands, far from their known feeding areas.

“It’s been a mystery where the whales that feed in the summer in the Bering Sea and in the Aleutians off Alaska go in the winter to breed. Many just don’t seem to show up in the known wintering grounds,” Lammers said. “This area in the monument beyond Gardner Pinnacles might provide some clues.”

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument is one of the largest marine protected areas in the world. It is co-managed by NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, NOAA Fisheries, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the state of Hawaiʻi and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

NOAA is considering designating marine portions of the monument as a national marine sanctuary under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act. Sanctuary designation would add a layer of protection to waters of the monument and not diminish existing protections.

The presence of koholā will be considered in monument management decisions, such as permitting, research, conservation and outreach. Humpback whales across the archipelago link the monument with Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, administered by a partnership of NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries and the state of Hawaiʻi through the Division of Aquatic Resources.

More research is needed in the far northwestern end of Papahānaumokuākea to identify the whales there and find out more about them. This requires physically visiting the remote areas of the monument where whale song was recorded, and conducting research including photo IDs, biopsy and collection of other information.

This data could be important for management decision-making. It will help answer questions about Hawaiʻi koholā, their identity, habits and patterns, and whether the monument is truly one of the lost breeding grounds of an endangered whale population.