Kaua‘i community asked to assist murdered, missing Native Hawaiian women and girls

Less than a quarter of the State of Hawai‘i population identifies as Native Hawaiian, descendants of the Polynesians who first settled the island chain approximately 1,600 years ago.

But more than a quarter of all missing girls in the state today are Native Hawaiian. They’re victims of a complex “invisible crisis” rooted in gender-based violence and the islands’ colonization by Western powers hundreds of years ago, according to a new report commissioned by the Hawai‘i State Commission on the Status of Women.

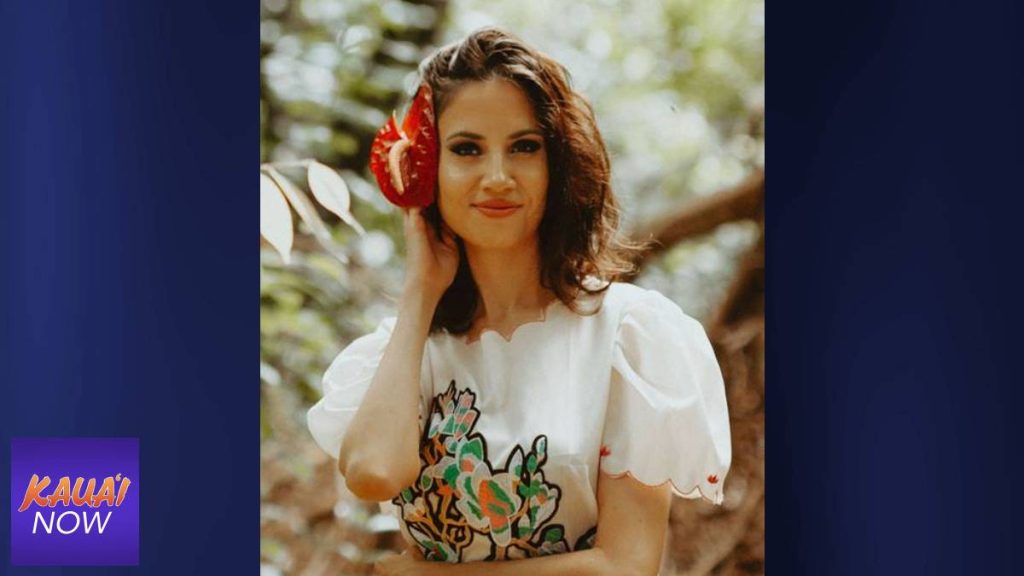

“Holoi ā nalo Wāhine ‘Ōiwi,” the Missing and Murdered Native Hawaiian Women and Girls Task Force report, was published late last month and authored by Kaua‘i community organizer and researcher Nikki Cristobal.

“Holoi ā nalo Wāhine ‘Ōiwi” means “to erase Native Hawaiian women completely.”

On Jan. 19, Cristobal will hold a community meeting at the Kaua‘i Philippine Cultural Center in Līhuʻe – and she wants you to help propel her work forward.

“We’d like to have it be informal,” she said. “We want whoever’s in the space feeling like the space is open enough to talk story.”

Cristobal was speaking from the corner of Rice and Kress streets in Līhuʻe, less than 300 feet from a blood-red mural she painted in May 2022, in observance of National Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirit Awareness Day.

“Two-spirit” refers to a person who identifies as having both a masculine and a feminine spirit, and is used by some Indigenous people to describe their sexual, gender and/or spiritual identity.

Cristobal’s blood-red mural depicts the face of a woman in profile, superimposed on a giant handprint. Island residents have added their own red handprints alongside it.

“I’m one person, and if this report is truly going to speak to the heart of our community and reach the people it needs to reach the most – whom I’m identifying as the victims and their families – we need to have these spaces where communities can feel their voices and their stories are being heard,” Cristobal said. “They’re part of generating this report. This report belongs to them.”

Cristobal’s December report represents Part One of a two-part project. It deals in quantitative or statistical data, while Part Two – due out in December 2023 – will record qualitative data, or interviews and testimonials provided by those affected by gender-based violence.

The issue has been dubbed the “invisible crisis” because there is so little information to go on, in part due to inconsistencies and gaps between various governmental and law enforcement agencies’ data-collection processes.

For example, in the State of Hawai‘i, each county police department is responsible for responding to and recording crimes using its own methods, which means the race of victims can often goes undocumented at the time of the incident. Other agencies collect sex data using the categories of male, female and Native Hawaiian, but do not specifically collect data on Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) females.

But the facts collected by Cristobal combine to reveal Native Hawaiian women and girls are outsized targets of sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse, suicide, poverty and more.

In 2021, the Missing Child Center Hawai‘i assisted law enforcement with 376 recoveries of missing children. These cases are only 19% of the estimated 2,000 cases of missing children in Hawai‘i each year.

The average profile of a missing child in the State of Hawai‘i – which has the eighth-highest rate of missing persons per capita in the nation at 7.5 missing people per 100,000 residents – is a 15-year-old Native Hawaiian female from O‘ahu.

The majority (43%) of sex trafficking cases in Hawai‘i are Kānaka Maoli girls trafficked in Waikīkī on O‘ahu.

U.S. military presence in Hawai‘i also plays a role, the report states. Seventy-four individuals, or 38% of those arrested for soliciting sex from a 13-year-old online through Operation Keiki Shield were active-duty military personnel, according to the Hawai‘i Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force.

Khara Jabola-Carolus, the executive director of the Hawaiʻi State Commission on the Status of Women, will join Cristobal at the Jan. 19 meeting in Līhuʻe. She has worked adjacent to U.S. military installations in South Korea and the Philippines.

“Anybody who lives in a military town … can attest to at least the fact that the military presence increases the number of exploiters and abusers, whether or not it’s disproportionate,” said Jabola-Carolus, who will also address the Kauaʻi County Committee on the Status of Women on Jan. 18. “It’s simply [due to] the nature of the institution: 80-plus percent male, socially isolated, younger, have money to burn, and are not rooted in accountability to local communities and families in the way that we as residents are.”

Cristobal has found no evidence of crimes against Native Hawaiian women and girls stemming from the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility at Barking Sands on the West Side of Kaua‘i. That’s in part due to the great lack of pertinent data available on Hawai‘i’s neighbor islands. (PMRF is also a relatively small training and testing site – a far cry from Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam on O‘ahu, where tens of thousands of people connected to the U.S. Navy and Air Force live and operate.)

“The reason you see O‘ahu and the Big Island represented so much in the data, is because those are the people who had the most data to give us,” Cristobal said. “That’s part of the reason we’re doing this community gathering. This first report really is trying to inspire people to get on board in terms of working with us, to get us data from their respective agencies, services and departments … Long story short, there’s just a lack of data for us to even understand what’s going on Kaua‘i versus the other islands.”

The report was mandated by the State Legislature in 2021 to both research the issue of murdered and missing Native Hawaiian women and girls and carve a path forward.

The biggest takeaway of Part One of the report is there is a critical need for more structured, systematic and streamlined data collection between governmental agencies.

The report, which will be sent to the State Legislature, describes itself as a “stepping stone.”

“It will take many more years of targeted efforts in research, policy and practice to gain the data necessary to understand the full scope of violence against [Native Hawaiian women and girls] and implement recommendations that can prevent this violence from continuing,” the report concluded.

Editor’s note: this story has been changed to reflect data collection regarding Hawai‘i’s māhū (two-spirit) community did not fall within the purview of the “Holoi ā nalo Wāhine ‘Ōiwi” report. A previous version indicated otherwise. We regret the error.