Hawaiian Corals Show Surprising Resilience to Warming Oceans

A new study that included researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi is painting a more optimistic picture of how Hawaiian corals are faring in warmer, more acidic oceans.

According to a press release from UH, a long-term study of Hawaiian coral species, including authors from the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, found that the three coral species studied experienced significant mortality under conditions that simulated ocean temperatures and acidity expected in the future — up to about half of some of the species died. But none of them completely died off — and some actually were thriving by the end of the study.

“It’s clear that corals are in a lot of trouble due to climate change, but our study also makes it clear that there are reasons for hope,” said Chris Jury, postdoctoral researcher at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology and study co-author.

Results showed that 61% of corals exposed to the warming conditions survived, compared to 92% exposed to current ocean temperatures.

The research, published in Scientific Reports, was led by a doctoral student at Ohio State University, Rowan McLachlan, who is now at Oregon State University.

While the findings are optimistic, they are also more realistic than previous studies.

The study lasted 22 months — much longer than most similar research, which often spans days and up to five months. In addition, the researchers were careful to create real-life conditions.

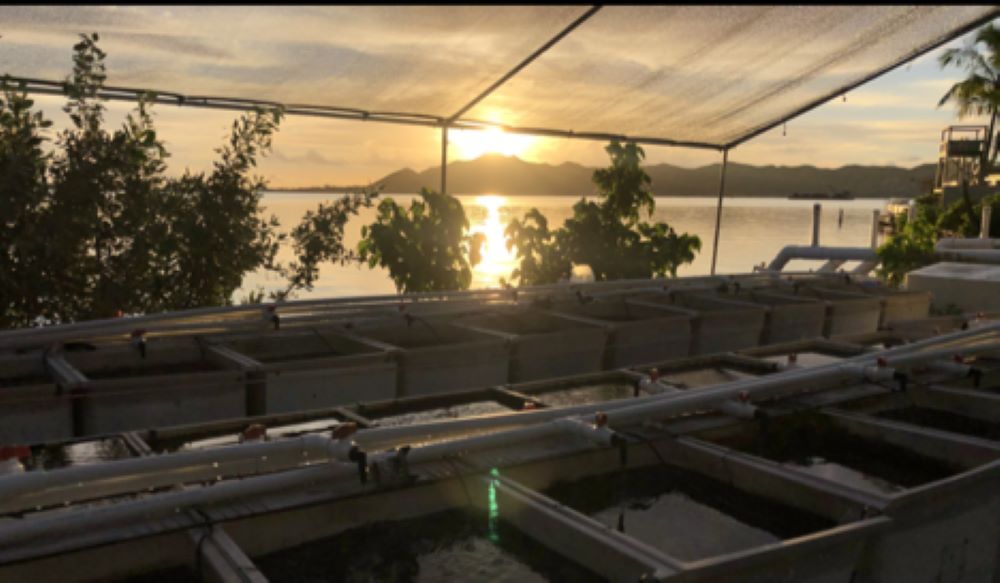

Test corals were put in outside tanks designed to mimic ocean reefs by including sand, rocks, starfish, urchins, crabs and fish. These tanks also allowed natural variability in temperature and pH levels throughout the course of each day and throughout seasons, as corals would have experienced in the ocean.

“It’s a difficult challenge to replicate the natural system,” said Jury in the press release. “That’s why we conducted this long-term study under realistic conditions, to get as close as possible to actual coral reefs.”

Samples of the three most common coral species in Hawaiʻi, Montipora capitata, Porites compressa and Porites lobata, were placed in tanks with four different conditions: control tanks with current ocean conditions, an ocean acidification condition, an ocean warming condition and a condition that combined warming and acidification.

The two Porites species were more resilient than M. capitata in the combined warming and acidification condition. Throughout the course of the study, survival rates were 71% for P. compressa, 56% for P. lobata and 46% for M. capitata.

“Of the coral that survived, especially the Porites species, they were coping well, even thriving,” said McLachlan in the release. “They were able to adapt to the above-average temperature and acidity.”

The two Porites species’ findings might offer particular hope, as they are among the most common types of coral around the world and they have a key role in reef building.

While this study does lead to reasons for optimism, it does not mean corals face no threat under climate change. Further, the study didn’t include local stressors such as pollution and overfishing that might have additional negative impacts on corals in some areas.

“Reefs are being assaulted on multiple fronts, from ocean warming and acidification, to local impacts, such as destructive fishing practices, sedimentation and coastal pollution,” Jury said in the release. “These are serious problems, but they are also fixable problems. With sensible action, we can help to ensure that there will still be healthy coral reefs during our lifetimes, and for the generations that come after us.”